Congress should

40. Social Security

• restore Social Security to long-term sustainable solvency; and

• allow younger workers to privately invest a portion of their Social Security payroll taxes through individual accounts.

Although few political candidates wanted to discuss it, the Social Security system faces severe financial pressures. Social Security's long-term unfunded liabilities now total $32.1 trillion. Congress's failure to act is threatening America's economic stability and promises to bury our children and grandchildren under a mountain of debt. Reform is not an option, it is a necessity, and Congress should act now.

But all Social Security reforms are not equal. Raising taxes and cutting benefits would have their own economic costs and would make a bad deal even worse for today's younger workers. However, by allowing younger workers to privately invest their Social Security taxes through individual accounts, we can

• help restore Social Security to long-term solvency, without massive tax increases;

• provide workers with higher benefits than Social Security would otherwise be able to pay;

• create a system that treats women, minorities, and young people more fairly;

• increase national savings and economic growth;

• allow low-income workers to accumulate real, inheritable wealth for the first time in their lives; and

• give workers ownership and control over their retirement funds.

Table 40.1

PAYGO Social Security System

| Generation | Period 1 | Period 2 | Period 3 | Period 4 |

| 0 | Retired benefits |

Dead | Dead | Dead |

| 1 | ↑ Working ↑ contributions |

Retired benefits |

Dead | Dead |

| 2 | Unborn | ↑ Working ↑ contributions |

Retired benefits |

Dead |

| 3 | Unborn | Unborn | ↑ Working ↑ contributions |

Retired benefits |

| 4 | Unborn | Unborn | Unborn | ↑ Working ↑ contributions |

SOURCE: Thomas Siems, "Reengineering Social Security for the New Economy," Cato InstituteSocial Security Paper no. 22, January 23, 2001.

The Looming Crisis

Social Security is a "pay-as-you-go" (PAYGO) program, in which Social Security taxes are used to immediately pay benefits for current retirees. It is not a "funded plan," in which contributions are collected and invested in financial assets and then liquidated and converted into a pension at retirement. Rather, it is a simple wealth transfer from current workers to current retirees.

Table 40.1 shows a basic model of overlapping generations: people are born in every time period, live for two periods (the first as workers, the second as retirees), and finally die. As time passes, older generations are replaced by younger generations. The columns represent successive time periods, and the rows represent successive generations. Each generation is labeled by the period of its birth, so that Generation 1 is born in Period 1, and so on. In each period, two generations overlap, with younger workers coexisting with older retirees.

In Table 40.1, a PAYGO pension system provides a start-up bonus to Generation 0 retirees by taking contributions from Generation 1 workers to pay benefits to those already retired. Thus, Generation 0 retirees receive a windfall because they never paid taxes into the system. Subsequent generations both pay taxes and receive benefits. There is no direct relationship between taxes paid and benefits received.

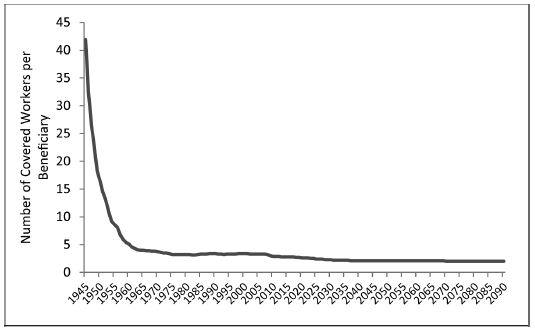

Figure 40.1

Worker to Beneficiary Ratio, 1945–2090

SOURCE: Social Security Administration, "The 2016 Annual Report of the Board of Trustees of the Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance and Federal Disability Insurance Trust Funds," Table IV.B3, Covered Workers and Beneficiaries, Calendar Years 1945–2090. Washington: Government Printing Office, 2016.

As long as the wage base supporting Social Security grows faster than the number of recipients, the program can continue to pay higher benefits to those recipients. But the growth in the labor force has slowed dramatically. In 1950, for example, there were 16.5 covered workers for every retiree receiving benefits from the program. Since then, Americans have been living longer and having fewer babies. As a result, there are now just 2.8 covered workers per beneficiary; and by 2034, there will be only 2.2 (Figure 40.1). Real wage growth (especially in wages below the payroll tax cap) has not been nearly fast enough to offset this demographic shift.

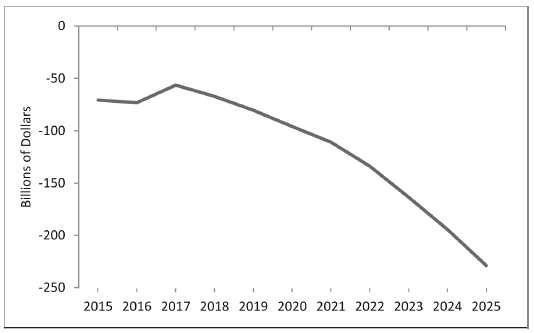

As Figure 40.2 shows, Social Security is already running a cash-flow deficit. In 2016, for instance, the program will pay out roughly $70 billion more in benefits than it takes in through taxes. That might seem a small amount of money in a world of trillion-dollar deficits, but without reform this shortfall will continue to grow. Very soon Social Security's deficit will reach levels that threaten to explode our overall budget deficit. Along with Medicare and Medicaid, Social Security will be one of the major drivers of our country's long-term debt.

Figure 40.2

Cash Flow Deficit, 2015–2025

SOURCE: Social Security Administration, "The 2016 Annual Report of the Board of Trustees of the Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance and Federal Disability Insurance Trust Funds," Table IV.A3, Operations of the Combined OASI and DI Trust Funds, Calendar Years 2011–2025. Washington: Government Printing Office, 2016.

NOTE: OASI = Old-Age and Survivors Insurance; DI = Disability Insurance. Intermediate scenario for years 2016–2025: payroll tax contributions and taxation of benefits are included, while net interest income is not.

In theory, of course, Social Security is supposed to continue paying benefits by drawing on the Social Security Trust Fund until 2034, after which the Trust Fund will be exhausted. At that point, by law, Social Security benefits will have to be cut by approximately 21 percent.

In reality, the Social Security Trust Fund is not an asset that can be used to pay benefits. Perhaps the best description of the Trust Fund can be found in the Clinton administration's fiscal year 2000 budget:

These [Trust Fund] balances are available to finance future benefit payments and other Trust Fund expenditures — but only in a bookkeeping sense… . They do not consist of real economic assets that can be drawn down in the future to fund benefits. Instead, they are claims on the Treasury that, when redeemed, will have to be financed by raising taxes, borrowing from the public, or reducing benefits or other expenditures. The existence of large Trust Fund balances, therefore, does not, by itself, have any impact on the Government’s ability to pay benefits.

Even if Congress can find a way to redeem the bonds, the Trust Fund surplus will be completely exhausted by 2034. At that point, Social Security will have to rely solely on revenue from the payroll tax — but that revenue will not be sufficient to pay all promised benefits. Overall, Social Security faces unfunded liabilities of $32.1 trillion over the infinite horizon. Clearly, Social Security is not sustainable in its current form. That means that Congress will again be forced to resort to raising taxes and/or cutting benefits to enable the program to stumble along.

In fact, the Social Security statement mailed to workers contains this caveat:

Your estimated benefits are based on current law. Congress has made changes to the law in the past and can do so at any time. The law governing benefit amounts may change because, by 2034, the payroll taxes collected will be enough to pay only about 79 percent of scheduled benefits.

Other Issues with Social Security

Social Security taxes are already so high, relative to benefits, that Social Security has quite simply become a bad deal for younger workers, providing a poor, below-market rate of return. This poor rate of return means that many young workers' retirement benefits will be far lower than if they were able to invest those funds privately.

In addition, Social Security taxes displace private savings options, resulting in a large net loss of national savings, reducing capital investment, wages, national income, and economic growth. Moreover, by increasing the cost of hiring workers, the payroll tax substantially reduces wages, employment, and economic growth as well.

After all the economic analysis, however, perhaps the single most important reason for transforming Social Security into a system of individual accounts is that it would give American workers true ownership of and control over their retirement benefits.

Many Americans believe that Social Security is an "earned right." That is, because they have paid Social Security taxes, they are entitled to receive Social Security benefits. The government encourages this belief by referring to Social Security taxes as "contributions," as in the Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA). However, in the case of Flemming v. Nestor, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that workers have no legally binding contractual or property right to their Social Security benefits and those benefits can be changed, cut, or even taken away at any time.

As the Court stated, "To engraft upon Social Security a concept of 'accrued property rights' would deprive it of the flexibility and boldness in adjustment to ever changing conditions which it demands." That decision built on a previous case, Helvering v. Davis, in which the Court had ruled that Social Security is not a contributory insurance program, stating that "the proceeds of both the employer and employee taxes are to be paid into the Treasury like any other internal revenue generally, and are not earmarked in any way."

In effect, Social Security turns older Americans into supplicants, dependent on the political process for their retirement benefits. If they work hard, play by the rules, and pay Social Security taxes their entire lives, they earn the privilege of going hat in hand to the government and hoping that politicians decide to give them some money for retirement.

Options for Reform

There are few options for dealing with the problem. This is not an opinion shared only by supporters of individual accounts. As former president Bill Clinton pointed out, the only ways to keep Social Security solvent are to

1. raise taxes;

2. cut benefits; or

3. get a higher rate of return through private capital investment.

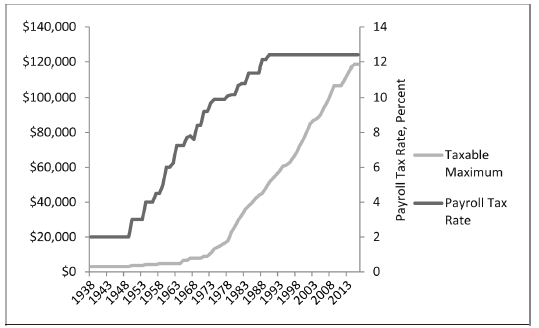

Certainly, throughout its history, Social Security taxes have been raised frequently to keep the system financially viable. The initial Social Security tax was 2 percent (split between the employer and employee), capped at $3,000 of earnings. That made for a maximum tax of $60. Since then, as Figure 40.3 shows, the payroll tax rate and the ceiling at which wages are subject to the tax have been raised a combined total of 67 times. Today, the tax is 12.4 percent, capped at $118,500, for a maximum tax of $14,694. Even adjusting for inflation, that represents more than an 800 percent increase.

Alternatively, Congress can reduce Social Security benefits. Restoring the program to solvency would require an immediate 16 percent cut to benefits. If reform is delayed until, say, 2034, the required cut would grow to 23 percent. Suggested changes include raising the retirement age further, trimming cost-of-living adjustments, means testing, or changing the wage-price indexing formula.

Figure 40.3

Payroll Tax Rate and Taxable Maximum Increases, 1938–2013

SOURCE: Social Security Administration.

Obviously, there are better and worse ways to make these changes. But, as described above, most younger workers will receive returns far below those provided by private investment. Some will actually receive less in benefits than they pay into the system, a negative return. Both tax hikes and benefit reductions further reduce the return that workers can expect on their contributions (taxes).

Perhaps the best way to reduce Social Security benefits would be to change the formula used to calculate the initial benefit so that benefits are indexed to price inflation rather than national wage growth. Since wages tend to grow at a rate roughly one-percentage point faster than prices, such a change would hold future Social Security benefits constant in real terms but would eliminate the benefit escalation that is built into the current formula. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that this change would reduce scheduled outlays by 7 percent in 2040 and 40 percent by 2080. This reform would result in the largest reduction in the actuarial shortfall of any options that the Congressional Budget Office analyzed, representing an 80 percent improvement. Variations on this approach would apply the formula change only to higher-income seniors, preserving the current wage-indexed formula for low-income seniors.

Table 40.2

Funded Social Security System

| Generation | Period 1 | Period 2 | Period 3 | Period 4 |

| 0 | Retired | Dead | Dead | Dead |

| 1 | Working → contributions |

Retired benefits |

Dead | Dead |

| 2 | Unborn | Working → contributions |

Retired benefits |

Dead |

| 3 | Unborn | Unborn | Working → contributions |

Retired benefits |

| 4 | Unborn | Unborn | Unborn | Working → contributions |

SOURCE: Thomas Siems, "Reengineering Social Security for the New Economy," Cato Institute Social Security Paper no. 22, January 23, 2001.

Better Reform: Personal Accounts

Ultimately, benefit reductions or tax increases are the only ways to restore Social Security to permanent sustainable solvency. But Social Security taxes are already so high, relative to benefits, that Social Security has quite simply become a bad deal for younger workers, providing a low, below-market rate of return. It makes sense, therefore, to combine any reduction in government-provided benefits with an option for younger workers to save and invest a portion of their Social Security taxes through individual accounts.

Table 40.2 shows what that would mean. Unlike the current Social Security system, each working generation's contributions actually would be saved and would accumulate as time passes. The accumulated funds, including the returns earned through real investment, would then be used to pay that generation's benefits when they retire. Under a funded system, there would be no transfer from current workers to current retirees. Each generation pays for its own retirement.

In a funded system, there is a direct link between contributions and benefits. Each generation receives benefits equal to its contribution plus the returns the investments earn. And because real investment takes place and the rate of return on capital investment can be expected to exceed the growth in wages, workers can expect to receive higher returns than under the current system.

Moving to a system of individual accounts would allow workers to take advantage of the potentially higher returns available from capital investment. In a dynamically efficient economy, the return on capital will exceed the rate of return on labor and therefore will be higher than the benefits that Social Security can afford to pay. In the United States, the return on capital has generally run about 2.5 percentage points higher than the return on labor.

True, capital markets are both risky and volatile. But private capital investment remains remarkably safe over the long term. For example, a 2012 Cato Institute study looked at a worker retiring in 2011, near the nadir of the stock market's recession-era decline. If that worker had been allowed to invest the employee half of the Social Security payroll tax over his working lifetime, he would have retired with more income than if he relied on Social Security. Indeed, even in the worst-case scenario, a low-wage worker who invested entirely in bonds, the benefits from private investment would equal those from traditional Social Security. While there are limits and caveats to this type of analysis, it clearly shows that the argument that private investment is too risky compared with Social Security does not hold up.

Low-income workers would be among the biggest winners under a system of privately invested individual accounts. Private investment would pay low-income workers significantly higher benefits than can be paid by Social Security. And that does not take into account the fact that blacks, other minorities, and the poor have below-average life expectancies. As a result, they tend to live fewer years in retirement and collect less in Social Security benefits than do whites. In a system of individual accounts, they would each retain control over the funds paid in and could pay themselves higher benefits over their fewer retirement years, or leave more to their children or other heirs.

The higher returns and benefits of a private, invested system would be most important to low-income families, as they most need the extra funds. The funds saved in the individual retirement accounts, which could be left to the children of the poor, would also greatly help families break out of the cycle of poverty. Similarly, the improved economic growth, higher wages, and increased jobs that would result from an investment-based Social Security system would be most important to the poor. Without reform, low-income workers will be hurt the most by the higher taxes or reduced benefits that will be necessary if we continue on our current course.

In addition, with average- and low-wage workers accumulating large sums in their own investment accounts, the distribution of wealth throughout society would become far broader than it is today. No policy proposed in recent years would do more to expand capital ownership than allowing younger workers to invest a portion of their Social Security taxes through personal accounts. Even the lowest-paid American worker would benefit from capital investment.

Cato's Social Security Plan

• Individuals will be able to privately invest 6.2 percentage points of their payroll tax in individual accounts. Those who choose to do so will forfeit all future accrual of Social Security benefits.

• Individuals who choose individual accounts will receive a recognition bond based on past contributions to Social Security. The zero coupon bonds will be offered to all workers who have contributed to Social Security, regardless of how long they have been in the system, but will be offered on a discounted basis.

• Allowable investment options for the individual accounts will be based on a three-tier system: a centralized, pooled collection and holding point; a limited series of investment options, with a life-cycle fund as a default mechanism; and a wider range of investment options for individuals who accumulate a minimum level in their accounts.

• At retirement, individuals will be given the option of purchasing a family annuity or taking a programmed withdrawal. The two options will be mandated only to the level needed to provide an income above a certain minimum. Funds in excess of the amount required to achieve that minimum level of retirement income can be withdrawn in a lump sum.

• Individuals who accumulate sufficient funds within their account to allow them to purchase an annuity that will keep them above a minimum income level in retirement will be able to opt out of the Social Security system in its entirety.

• The remaining 6.2 percentage points of payroll taxes will be used to pay transition costs and to fund disability and survivors benefits. Once, far in the future, transition costs are fully paid for, this portion of the payroll tax will be reduced to the level necessary to pay survivors and disability benefits.

• The Social Security system will be restored to a solvent pay-as-you-go program before individual accounts are developed and implemented. Workers who choose to remain in the traditional Social Security system will receive whatever level of benefits Social Security can pay with existing Trust Fund levels. The best method for restoring the system’s solvency is to change the initial benefit formula from wage indexing to price indexing.

Conclusion

Social Security is not sustainable without reform. Simply put, it cannot pay promised future benefits with current levels of taxation. Every year that we delay reforming the system increases the size of Social Security’s shortfall and makes the inevitable changes more painful.

Raising taxes or cutting benefits will only make a bad deal worse. At the same time, workers have no ownership of their benefits, and Social Security benefits are not inheritable. That reality is particularly problematic for low-wage workers and minorities. Perhaps most important, the current Social Security system gives workers no choice or control over their financial future.

It is long past time for Congress to act.

Suggested Readings

Gokhale, Jagadeesh. Social Security: A Fresh Look at Policy Alternatives. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2010.

Miron, Jeffrey. Fiscal Imbalance: A Primer. Washington: Cato Institute, 2015.

Pinera, Jose. “Empowering Workers: The Privatization of Social Security in Chile.” Cato’s Letters no. 10, May 1996.

Tanner, Michael. “The 6.2 Percent Solution: A Plan for Reforming Social Security.” Cato Institute Social Security Paper no. 32, February 17, 2004.

—. Going for Broke. Washington: Cato Institute, 2015.

—. “Social Security, Ponzi Schemes, and the Need for Reform.” Cato Institute Policy Analysis no. 689, November 17, 2011.

—. “Still a Better Deal: Private Investment vs. Social Security.” Cato Institute Policy Analysis no. 692, February 13, 2012.

Tanner, Michael, ed. Social Security and Its Discontents: Perspectives on Choice. Washington: Cato Institute, 2004.