The debate between Cato adjunct scholar Shirley Svorny and the Manhattan Institute’s Ted Frank wraps up at Point of Law today.

Cato at Liberty

Cato at Liberty

Topics

Supreme Court Takes Up Arizona Immigration Law

The Supreme Court has agreed to review Arizona v. United States, the case regarding SB 1070, the Arizona law (only) four sections of which have been enjoined by the lower courts: requiring police to check the immigration status of anyone they have lawfully detained whom they have reasonable suspicion to believe may be in the country illegally; making it a state crime to violate federal alien registration laws; making it a state crime for illegal aliens to apply for work, solicit work in a public place, or work as an independent contractor; and permitting warrantless arrests where the police have probable cause to believe that a suspect has committed a crime that makes him subject to deportation. For my previous analysis of SB 1070 and the legal challenges to it, see here, here, here, and here.

By taking up this case, the Supreme Court is wisely nipping in the bud the proliferation of state laws aimed at addressing our broken immigration system. One way or another, states will know how far they can go in addressing issues relating to illegal immigrants, whether the concern is crime, employment opportunities (providing or restricting them), registration requirements, or even so-called sanctuary cities.

Of course, states wouldn’t be getting into this mess if the federal government — elected officials of both parties — hadn’t abdicated its responsibility to fix a system that serves nobody’s interests: not big business or small business, not the rich or the poor, not the most or least educated, not the economy or national security, and certainly not the average taxpayer. For their part, SB 1070 and related laws in Alabama, Georgia, and elsewhere are (with small exception) constitutional — the state laws are merely mirroring federal law, not conflicting with it or otherwise intruding on federal authority over immigration — but bad public policy. (For more on both these conclusions, read my SCOTUSblog essay from last summer.)

What this country needs is a comprehensive reform that obviates the sort of ineffectual half-measures the states are left with given Congress’s shameless refusal to act. It’s not very often that Cato calls for the federal government to do something, but the immigration system is quite possibly the most screwed-up part of the federal government — which of itself is a significant statement coming from someone at Cato — and one that is so incredibly counterproductive to American liberty and prosperity.

The Court will hear Arizona v. United States in the spring. For more immigration-reform developments, see this note in today’s Wall Street Journal and my blogpost on Utah’s plan, which the federal government has also since sued to enjoin.

Fed Apologists Gone Wild

In today’s Washington Post, Robert Samuelson laments in “Fed bashing gone wild” that public concerns about the Federal Reserve’s behavior during the financial crisis undermine the Fed’s ability to save our economy. In Samuelson’s words: “If the Fed is stigmatized for succeeding, we may find that next time it won’t be there.” I’m struggling to figure out what “success” Samuelson is talking about.

He begins his piece relating how the Fed was created in reaction to the Panic of 1907 but that inaction on its part made the Great Depression worse. His concern: “Criticism that the Fed was too active in 2008 may induce it to be too passive in another crisis.” He conveniently leaves out the NY Fed’s role in helping create the 1920’s stock market bubble, which was a direct result of its efforts to manage the dollar-sterling exchange rate. But that omission shouldn’t be surprising as Samuelson also fails to mention the Fed’s role in inflating the recent housing bubble (how is three years of a negative real federal funds rate ever good policy?).

Implying that the massive number of bank failures in the Great Depression would have been avoided with a more active Fed also ignores, or “revises”, history. What about Canada, it also had a depression, but lacked any central bank and did not witness any bank failures? There’s a large academic literature on banking stability during the Great Depression, those interested in facts couldn’t do much better than starting here.

Of course Samuelson also repeats the same myth that we’d be in another Depression had not the Fed rescued, under very generous terms, the financial system. All due respect to Mark Zandi’s opinion, but serious research has found that “from the start of the financial crisis (third quarter of 2007) to its peak (first quarter of 2009), both large and investment-grade non-financial firms show no evidence of suffering from an exceptional systemic credit contraction.” The “freeze” in the commercial paper was only in the bank-backed ABS market, not the industrial side. This was never about helping Harley-Davidson make pay-roll, it was always about bailing out Citibank and the like.

The Federal Reserve has a long record of failure. I don’t see it as an exaggeration to say its been the cause of crisis far more often than the cure. If we simply look the other way, as Samuelson would have us do, then we are certain to have many more loose-money driven booms and busts, resulting in additional financial crises.

Monetary and Fiscal Policy at Cato Unbound

This month we’re talking macroeconomics at Cato Unbound. Tim Congdon kicks things off with an essay about the confused legacy of John Maynard Keynes. We have been told, again and again, that the United States is in a liquidity trap — because the federal funds rate can’t go below zero.

There are several problems with this often-repeated claim. First, even at a federal funds rate of zero, other instruments of monetary policy remain effective. Second, a central bank lending rate of zero is not at all what Keynes himself meant when he used the term “liquidity trap.” Third, what Keynes did mean is a source of considerable ambiguity, as necessitated by the simplified model he presented in his General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money. And finally, a liquidity trap that conforms to his model may never actually occur, at least not in the strict sense.

Advancing these claims is Tim Congdon, the United Kingdom’s leading monetarist and author of the recent book Money in a Free Society. He is joined by three other prominent economists, each with a slightly different view of the issue. They are Dean Baker, co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research; Don Boudreaux of George Mason University; and Robert Hetzel, an economist with the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

As always, Cato Unbound readers are encouraged to take up our themes and enter into the conversation on their own websites and blogs, or at other venues. Trackbacks are enabled. We also welcome your letters and may publish them at our option. Send them to jkuznicki at cato.org

No Wonder Romney Didn’t Mind Forcing People to Purchase Health Insurance

To Mitt Romney, $10,000 is no big deal.

Related Tags

European Central Bank Research Shows that Government Spending Undermines Economic Performance

Europe is in the midst of a fiscal crisis caused by too much government spending, yet many of the continent’s politicians want the European Central Bank to purchase the dodgy debt of reckless welfare states such as Spain, Italy, Greece, and Portugal in order to prop up these big government policies.

So it’s especially noteworthy that economists at the European Central Bank have just produced a study showing that government spending is unambiguously harmful to economic performance. Here is a brief description of the key findings.

…we analyse a wide set of 108 countries composed of both developed and emerging and developing countries, using a long time span running from 1970–2008, and employing different proxies for government size… Our results show a significant negative effect of the size of government on growth. …Interestingly, government consumption is consistently detrimental to output growth irrespective of the country sample considered (OECD, emerging and developing countries).

There are two very interesting takeaways from this new research. First, the evidence shows that the problem is government spending, and that problem exists regardless of whether the budget is financed by taxes or borrowing. Unfortunately, too many supposedly conservative policy makers fail to grasp this key distinction and mistakenly focus on the symptom (deficits) rather than the underlying disease (big government).

The second key takeaway is that Europe’s corrupt political elite is engaging in a classic case of Mitchell’s Law, which is when one bad government policy is used to justify another bad government policy. In this case, they undermined prosperity by recklessly increasing the burden of government spending, and they’re now using the resulting fiscal crisis as an excuse to promote inflationary monetary policy by the European Central Bank.

The ECB study, by contrast, shows that the only good answer is to reduce the burden of the public sector. Moreover, the research also has a discussion of the growth-maximizing size of government.

… economic progress is limited when government is zero percent of the economy (absence of rule of law, property rights, etc.), but also when it is closer to 100 percent (the law of diminishing returns operates in addition to, e.g., increased taxation required to finance the government’s growing burden – which has adverse effects on human economic behaviour, namely on consumption decisions).

This may sound familiar, because it’s a description of the Rahn Curve, which is sort of the spending version of the Laffer Curve. This video explains.

The key lesson in the video is that government is far too big in the United States and other industrialized nations, which is precisely what the scholars found in the European Central Bank study.

Another interesting finding in the study is that the quality and structure of government matters.

Growth in government size has negative effects on economic growth, but the negative effects are three times as great in non-democratic systems as in democratic systems. …the negative effect of government size on GDP per capita is stronger at lower levels of institutional quality, and ii) the positive effect of institutional quality on GDP per capita is stronger at smaller levels of government size.

The simple way of thinking about these results is that government spending doesn’t do as much damage in a nation such as Sweden as it does in a failed state such as Mexico.

Last but not least, the ECB study analyzes various budget process reforms. There’s a bit of jargon in this excerpt, but it basically shows that spending limits (presumably policies similar to Senator Corker’s CAP Act or Congressman Brady’s MAP Act) are far better than balanced budget rules.

…we use three indices constructed by the European Commission (overall rule index, expenditure rule index, and budget balance and debt rule index). …The former incorporates each index individually whereas the latter includes interacted terms between fiscal rules and government size proxies. Particularly under the total government expenditure and government spending specifications…we find statistically significant positive coefficients on the overall rule index and the expenditure rule index, meaning that having these fiscal numerical rules improves GDP growth for these set of EU countries.

This research is important because it shows that rules focusing on deficits and debt (such as requirements to balance the budget) are not as effective because politicians can use them as an excuse to raise taxes.

At the risk of citing myself again, the number one message from this new ECB research is that lawmakers — at the very least — need to follow Mitchell’s Golden Rule and make sure government spending grows slower than the private sector. Fortunately, that can happen, as shown in this video.

But my Golden Rule is just a minimum requirement. If politicians really want to do the right thing, they should copy the Baltic nations and implement genuine spending cuts rather than just reductions in the rate of growth in the burden of government.

Related Tags

Is the Problem in Italy and Greece a Lack of Demand?

Earlier this week Dean Baker took a shot at Robert Samuelson for claiming that the problems in Europe were because of the “runaway welfare” state. While I consider Baker to generally be quite thoughtful, I am not sure that comparing interest rates with levels of government spending really disproves Samuelson’s point. There is a lot that goes into differences in borrowing costs, especially across governments. Setting aside the fact that banking and financial regulations distort the government debt markets, we should also see differences due to “willingness to pay” and not just “ability to pay.” All else equal in terms of budgets, I’d still charge more to lend to Greece than Sweden.

Baker attributes the real problems in Europe to “too little demand.” Now I don’t know what the correct level of demand in any country is supposed to be, but for the level of problems we are witnessing in southern Europe, I’d suspect you’d need a pretty big hole in demand. If one buys into a standard Keynesian income-expenditure model of the economy, then a reasonable place to start looking would be final private consumption expenditures.

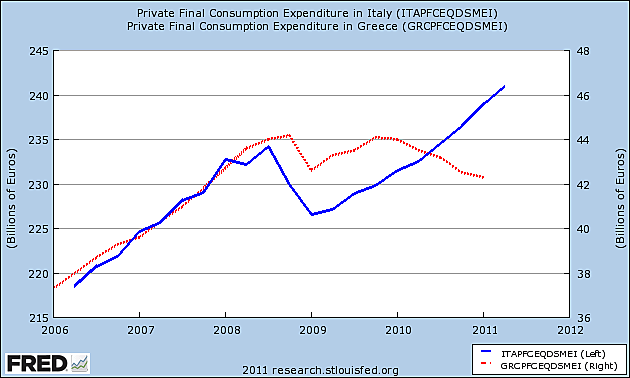

The chart below shows final private consumption expenditures for Greece (dotted line = right axis) and Italy (solid line = left axis). Yes, both had a pretty big drop at the end of 2008, but Italy seems to have been recovering steadily. In fact, consumption today in Italy appears about 3% higher than at the previous peak. Greece has not done so well, with consumption almost 5% below peak, but its still above the levels seen in 2007. Neither of these charts has been adjusted for inflation or population, but if demand is unusually “weak” then we’d be seeing deflation, so if anything these numbers likely understate actual trends in consumption.

I’m not going to pretend that I’m an expert on either the Italian or Greek economy, or that this chart proves anything. It does, however, suggest to me that the problems in Greece and Italy are unlikely due to some sort of Keynesian liquidity trap where people just aren’t spending.