The COVID-19 crisis and resulting recession will strain state government budgets. Unlike the federal government, the states are required to balance their general fund budgets each year. As the economy shrinks, state income and sales tax revenues will fall and budget gaps will rise.

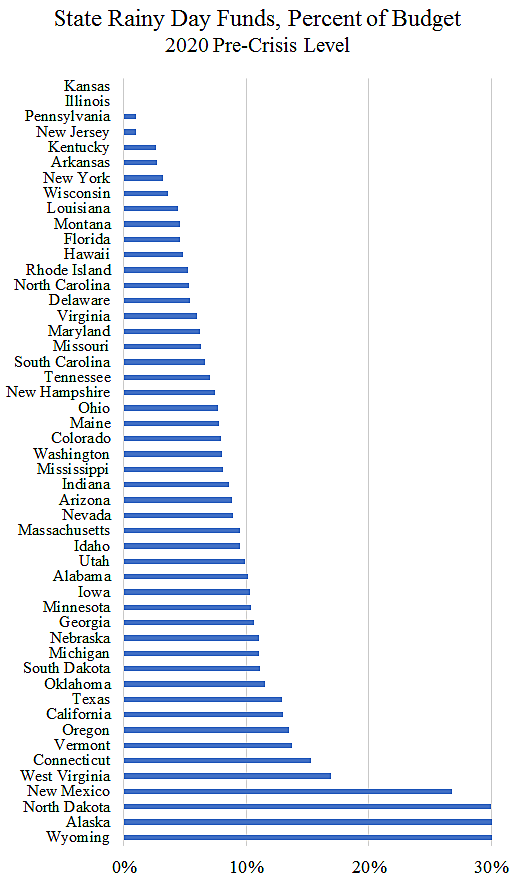

One way to fill budget gaps is to use state rainy day funds, which are also called budget stabilization funds. All states have such funds, but the mechanisms vary. The rules for fund deposits, withdrawals, and maximum fund sizes differ between the states. Some funds are constitutional and others are statutory. Reports by NCSL, Tax Foundation, and Pew provide details.

After the deep recession a decade ago, many states learned the lesson and have since grown their rainy day funds. NASBO reported in December that rainy day funds were projected to be an average 8.4 percent of annual general fund spending for fiscal year 2020, which compares to 4.8 percent going into the last recession in 2008. Today’s larger rainy funds will help the states weather the COVID-19 storm.

However, the size of state rainy day funds varies widely. The chart below shows NASBO data for projected fund sizes in 2020 before the crisis hit. News reports indicate that some states are already tapping these funds.

The chart indicates that some states have been such spendthrifts that, after a decade of economic growth, they have saved little or nothing. Illinois and Kansas have completely empty cupboards, while Pennsylvania and New Jersey have rainy day funds of just 1 percent of their budgets. The largest funds are in energy producing states, which build war chests to handle the strong cyclical ups and downs in their economies.

State leaders and economists did not foresee the COVID-19 crisis of 2020, nor they did not foresee the deep recession of a decade ago. That is why rainy day funds make a lot of sense. It is also why state governments should pay down debt during strong growth years, because downturns eventually arrive. Of course, the same is true of the federal government.

When growth resumes after the current crisis, the states should spend the next few years beefing up their rainy day funds to high levels. A few states—such as Illinois—need a radical overhaul of their budgeting processes because they can’t seem to save any money, even after years of growth. Aside from helping states weather storms, large rainy day funds make states less reliant on federal bailouts, they improve state credit ratings, and they strengthen the overall U.S. macroeconomy.

Notes: Data for 2020 was not available from NASBO for Georgia, Michigan, North Carolina, Oklahoma, and Wisconsin, so earlier data was used. I capped the chart at 30 percent. North Dakota was 30 percent, Alaska was 53 percent, and Wyoming was 109 percent.

Sarah Rapier assisted with this blog.