Today, the United States Senate approved the FY2021 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), which contains an amendment passed earlier this week, with little floor debate and by a 96–4 margin, that would provide billions of dollars in new federal support for the U.S. semiconductor industry, most notably tax credits and grants for the construction of new domestic manufacturing facilities. The House passed a similar bill with a similar amendment earlier this week, so the legislation now goes to conference, where the subsidies are expected to survive. The two main reasons for the Senate and House amendments (formerly a standalone bill called the “CHIPS Act”), as helpfully summarized by House co-sponsor and Foreign Affairs Committee Ranking Member Michael McCaul (R‑TX), are (1) to boost U.S. semiconductor manufacturing and jobs and (2) to prevent China from “dominating” the global semiconductor market:

Ensuring our leadership in the future design, manufacturing, and assembly of cutting edge semiconductors will be vital to United States national security and economic competitiveness. As the Chinese Communist Party aims to dominate the entire semiconductor supply chain, it is critical that we supercharge our industry here at home. In addition to securing our technological future, the CHIPS Act will create thousands of high-paying U.S. jobs and ensure the next generation of semiconductors are produced in the US, not China.

Similarly dire, China-centric statements have been issued by other supporters in Congress (see, e.g., these from Senators Doug Jones (D‑AL), Tom Cotton (R‑AR), or Chuck Schumer (D‑NY)), most of whom – unsurprisingly – appear to have semiconductor manufacturers in their states or districts that stand to profit from the new taxpayer funds. (Schumer’s statement, in classic fashion, actually emphasizes how this cash will help New York companies.)

The congressional statements, urgency and near-unanimity would lead a casual observer to believe that the U.S. semiconductor industry is in a truly-desperate position, hobbled by a heavily-subsidized, globally dominant China and in dire need of a massive and immediate injection of government support. That would not, however, be the reality – even assuming (erroneously) that “reshoring” global supply chains advances actually national security. Instead, numerous facts and analyses show the U.S. semiconductor industry to be in pretty good shape and the Chinese industry – while certainly subsidized – to not be the dangerous juggernaut that our elected officials claim.

Let’s first start with the U.S. industry. Most basically, Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) data show U.S. “Semiconductor and other electronic component manufacturing” to have increased substantially in recent years, topping $113.4 billion in real gross output and $88 billion in real value-added in 2018 (the last year for which detailed data are available). Real gross output for “Semiconductor and related device manufacturing” alone reached $64.9 billion; more detailed value-added data are not available.

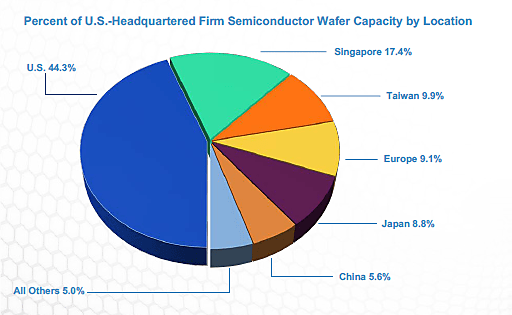

The Semiconductor Industry of America (SIA) further notes that there are commercial semiconductor manufacturing facilities (called “fabs”) in 18 states, employing more than 240,000 Americans, and that the United States has 12.5 percent of global semiconductor manufacturing capacity. And while the U.S. industry does indeed utilize fabs around the world, the largest share (44.3%) of that work remains in the United States while only small portion (5.6%) is in China:

The United States is also a top‑5 global exporter of semiconductors and related equipment, shipping almost $47 billion in goods falling under Harmonized System subchapters 8542 ($40.0 billion) and 8541 ($6.7 billion) last year. These and other data led the SIA to conclude in its 2020 “State of the U.S. Semiconductor Industry” report that “the semiconductor manufacturing base in the United States remains on solid footing.”

In terms of sales (not just manufacturing), moreover, the SIA reports that the U.S. industry is the global leader in market share, with “nearly half” of the entire world semiconductor market – a share that has been remarkably steady (ranging from the mid-40s to low-50s) since the late 1990s – and sales leadership in every major regional market, including China. Sales by U.S semiconductor firms also grew from $76.7 billion in 1999 to $192.8 billion in 2019 — a compound annual growth rate of almost 5%.

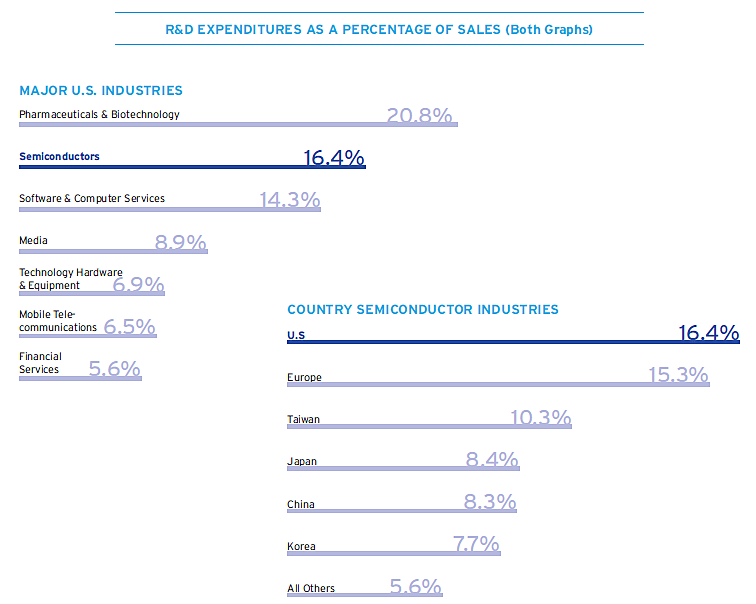

Beyond output and sales, the U.S. semiconductor industry has been a global leader in capital spending (“capex”) and research and development – a testament to not only their business acumen but also U.S. capital markets. SIA notes that total R&D and capital expenditures by U.S. semiconductor firms (including “fabless” companies) was $71.7 billion in 2019, growing steadily between 1999 and 2019 at a 6.2% annual rate. R&D expenditures hit $39.8 billion last year, constituting 16.4% of the industry’s total sales last year – a “R&D intensity” second only to pharmaceuticals in the United States and the highest in the world:

The U.S. industry’s capex has been similarly world-class: SIA reports that 2018 capital expenditures reached “an all-time high of $32.7 billion” and constituted 12.5% of sales in 2019, with only Korea having a larger global share of semiconductor capex last year:

Other data corroborate these findings. According to the U.S. National Science Board’s 2020 report on R&D Trends, U.S. computer and electronic (including semiconductor) companies spent more on R&D in 2016 (the last year available) than any other country surveyed – often many times more – with only South Korea’s sector having greater share of total or manufacturing R&D than the United States:

The BEA further calculates that foreign multinational corporations in 2017 spent $7.3 billion and $2.2 billion on R&D and capex, respectively, for their U.S. affiliates in the “semiconductors and other electronic components” sector, up from $4.4 billion and $1.9 billion in 2007. And U.S. semiconductor companies’ stock prices have steadily climbed over the last decade. Clearly, the sector remains quite attractive.

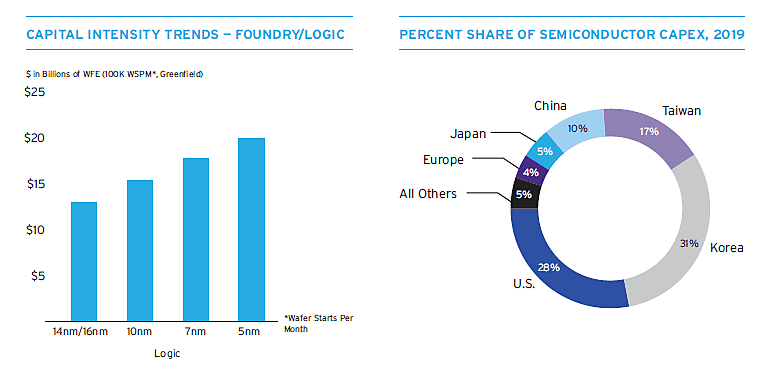

As a result of this investment, the SIA notes that in 2019 the United States remained at or near the “leading edge” of current semiconductor technology (“essentially neck-and-neck [with Korea and Taiwan] in logic process technology as all three nations have raced to bring leading-edge 7/10 nm technology to market”). Taiwan’s TSMC has reportedly begun production of 5 nm chips, but these are just now hitting the market. U.S.-based Intel, meanwhile, is racing to catch up after making what appears to be a bad bet on 10 nm wafers a few years ago.

In short, the U.S. semiconductor industry may have temporarily lost its global manufacturing lead, but it’s still quite healthy – in many ways still globally dominant – and is investing billions of its own dollars to stay at or near the top in the future (something the companies’ shareholders seem to think they will accomplish).

China, on the other hand, remains years behind industry leaders in the United States, Korea and Taiwan, and it might never catch up, despite (or perhaps because of) boatloads of subsidies and industrial planning. In fact, a detailed 2019 report on China’s semiconductor industry by the United States International Trade Commission showed that it is precisely this planning and subsidization, along with human capital constraints and international competition, holding back China’s industry:

China’s semiconductor industrial plans have lacked defined goals and clear implementation strategies, and have been hampered by bureaucratic redundancies. Relying heavily on state-owned enterprises (SOEs), these plans have been hindered by poor management, production inefficiencies, and a level of support from the state that resulted in profligate spending. In particular, the SOEs lack absorptive and innovative capacity, producing chips that fail to gain commercial traction….

China’s current plans look more sustainable, but still rely heavily on well-funded but poorly directed SOEs that benefit from a market that lacks true competition. At the same time, some of the larger challenges that hindered previous development, such as a dearth of human capital, remain unaddressed.

The report thus concludes that China’s industrial planning efforts – the express basis for new U.S. government subsidies – “will not achieve their desired success,” a conclusion shared by many other industry experts. In fact, analysts recently told the Wall Street Journal that China’s national champion, Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp. (SMIC), “is still around five years behind TSMC and the gap will likely remain in the foreseeable future.”

Some threat.

Finally, there is the question of whether these new U.S. subsidies will achieve their “national security” or economic objectives; here too, there’s reason for concern (beyond the aforementioned point about re-shoring and security). Previous U.S. government support for the semiconductor industry has ranged from “checkered” to total debacle. In the 1980s, for example, U.S. efforts to support the semiconductor industry through protectionism and industrial policy – then deemed necessary to fend off Japan – cost U.S. computer companies and the economy billions of dollars; encouraged offshoring of high-tech industries and political dysfunction in the United States and Japan; failed to boost U.S. semiconductor production capacity; and actually strengthened Japanese and Korean competitors. Indeed, government policymakers ended up picking the entirely wrong product to subsidize and protect in its attempt to ensure “the future of U.S. global technology leadership.” Yikes.

More recent history might not be much better. TSMC, for example, just scored its own U.S. billions to produce semiconductors in Arizona, but the Wall Street Journal reports that, although construction will begin next year, actual production is targeted for 2024 (at best). Once operational, moreover, the fab will make only 20,000 wafers a month (“making it a relatively small facility for a company that made more than 12 million wafers last year alone”), and it “would likely not be at the leading edge of chip-making technology” because TSMC and other companies plan to move to even smaller, 3 nm chips in the next few years. And, while heralded as a “national security” victory by Secretary of State Pompeo, the aforementioned article notes that “TSMC’s project would also not likely address a desire by the Pentagon to have a U.S. firm make more chips for defense purposes.” (On the other hand, the project, has been deemed a political “win” for President Trump in a state that he needs in 2020. So it’s got that going for it, which is nice.)

Lastly, these subsidies could actually hurt U.S. semiconductor exports, which as noted above are significant, and thus end up costing U.S. companies revenue or global market share. As I explained in a 2012 Cato Institute paper, global trade rules and national “countervailing duty” laws allow nations to slap duties on subsidized imports that are found to have “injured” the nation’s own domestic industry. These cases are especially easy where, as here, the subsidies expressly target a specific industry in law, and they ticked up the last time the United States joined the “global subsidies race” in 2009. Another round of “stimulus,” especially for major exporting industry, could do the same today.

So, to recap: the House and Senate just fast-tracked billions in direct government subsidies (not just R&D support) to U.S. semiconductor manufacturers that are, by their own account, “on solid footing,” in order to counter a threat that, by the U.S. government’s own account, doesn’t actually exist – billions that, if history is any guide, won’t produce clear benefits and could actually harm the industry.

And who says Washington is broken?

Ironically, recent U.S. policy – in particular onerous new restrictions on high-skill immigration – could actually help China solve its human capital problem and thus boost its currently-low chances to become an actual player in the global semiconductor game. In a sane world, policymakers eager to help the U.S. semiconductor industry or to counter China’s high-tech ambitions would start there (and then move on to the tariffs costing U.S. chipmakers hundreds of millions of dollars) before ramming through billions of “emergency” taxpayer dollars to healthy companies. Even saner would be Congress and Washington policymakers having a serious debate about trade, industrial policy and national security, instead of just diving head-first into economic nationalism every time a lobbyist or industry group says the word “China.”

As this week’s votes make clear, unfortunately, such sanity seems to be in very short supply these days.