Dear Capitolisters,

In the pantheon of right-leaning economists, there’s a front row seat for Stanford’s Thomas Sowell. For those of you who don’t know Dr. Sowell, who turned a spry 90 last year and is still going strong, I recommend this recent tribute to some of his most important work, as well as this brand new documentary on his life. For me, two specific Sowell quotes stand out when thinking about public policy and the intersection of politics and economics:

-

When evaluating a policy proposal, always “think beyond stage one” and ask “and then what will happen?” (via his Applied Economics)

-

“There are no solutions, there are only tradeoffs ;;; and you try to get the best trade-off you can get, that’s all you can hope for.” (via this 2005 interview)

Both of these quotes come to mind when considering the new Biden/Democratic party proposal to raise the minimum wage, which was released last week and has a small-but-real chance of becoming law as part of the party’s massive COVID-19 relief package. Given that potential, as well as the release of some new economic research on the subject, now’s a perfect time to dig into the minimum wage issue, leaning on the two Sowell quotes above.

The Bill’s Basics

Before I do that, however, let’s start with the basics about the new proposal, the “Raise the Wage Act of 2021.” The bill has three main wage-related parts:

-

A series of annual increases to the federal minimum wage for all eligible employees, starting at $9.50 on Day One and ending at $15 an hour in 2025;

-

Automatic subsequent increases in the minimum wage tied to the median hourly wage of all employees;

-

Special rules for tipped employees, teenagers, and individuals with disabilities—groups that are now subject to special rules but would, under the new law, see their minimum wages gradually align with the new federal floor in a few years.

As The Dispatch’s Haley Byrd Wilt notes in a recent column, congressional Democrats appear willing to try to push this bill—and the rest of their $1.9 trillion proposal—through the Senate via “reconciliation,” which permits budgetary measures to pass the Senate with a bare majority (instead of a filibuster-proof one). Raising the minimum wage via reconciliation is, ahem, creative (to say the least), and there’s no guarantee that the Senate parliamentarian will go for it. There’s also still the question, as Haley notes, of whether Dems can get even 50 votes for the big COVID package. Nevertheless, some Senate Dems are hinting that they’ll just ignore the parliamentarian ruling, and a final vote tally is anyone’s guess at this stage. Thus, the full Biden relief package—and the minimum wage proposal buried therein—is a real possibility (albeit an uncertain one).

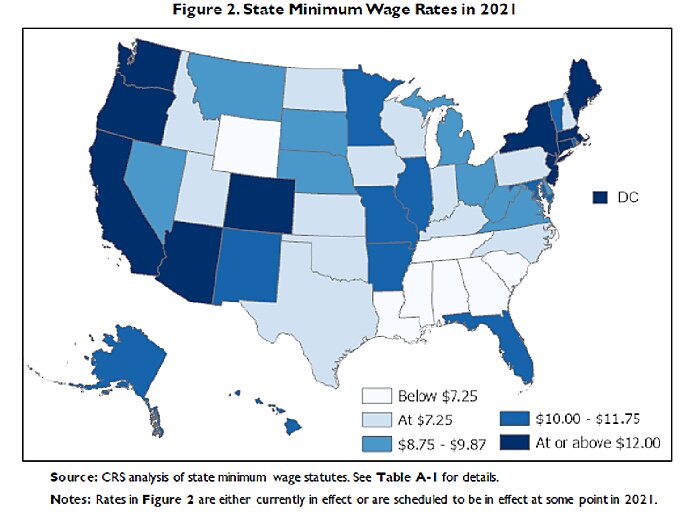

Should the bill become law, the raised minimum wage would have an immediate impact. As noted by Senate Democrats (quoting the Economic Policy Institute), the Raise the Wage Act would be the first national minimum wage hike since 2009 and “would increase wages for nearly 32 million Americans, including roughly a third of all Black workers and a quarter of all Latino workers.” Maybe those numbers are off a little one way or another, but there’s little doubt that the act would affect a lot of American workers, given where minimum wages are right now and where they’re scheduled to go. On the former, the Congressional Research Service shows us the states that currently impose minimum wages below $9.50 an hour and thus would see an immediate hike:

CRS details in a subsequent section that only six states (California, Connecticut, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey) and the District of Columbia have currently scheduled a statewide $15 an hour minimum wage by 2025. New York applies the wage to certain areas and employers, and two other states (Florida and Virginia) will hit $15 an hour in 2026.

Thus, the Raise the Wage Act would undoubtedly have a large impact—both immediately and over the next four years—for workers now making less than the proposed new minimum wage.

And Then What Will Happen?

Sowell teaches us that it’s imperative to think past “stage one” (here, the aforementioned wage increases). And that’s where the minimum wage debate really begins.

For years, it was widely accepted that minimum wages benefit certain low-wage workers directly but have significant additional costs—most notably higher prices for consumers and depressed employment for low-skilled workers whose wages suddenly exceeded their productivity (thus making them unprofitable for their employers). Recently, however, news reports, non-profits, and some left-leaning economists like Paul Krugman have begun to say—based on a handful of new economic studies—that raising the minimum wage doesn’t actually “cost jobs” or have other “large employment effects that some economists feared.” Indeed, one EPI economist recently urged policymakers “to pursue higher minimum wage levels … because past increases were effectively costless.”

Unfortunately, however, these readings of the economics literature tend to understate or misunderstand the downsides—in “stage two” and beyond—of minimum wage hikes. For starters, the vast majority of economic papers still find that minimum wages cost jobs, as shown in a new paper from economists David Neumark and Peter Shirley that examined every published analysis of the impact of minimum wage hikes on U.S. employment outcomes since 1992. My Cato colleague Ryan Bourne summarized these findings in a recent blog post:

-

The overwhelming majority of papers analyzing the U.S. estimate a negative effect on employment [i.e., fewer jobs or hours] of minimum wage hikes (79.3 percent of them). In fact more than half of all papers have a negative impact that is statistically significant at the 10 percent level or more.

-

The negative impact is stronger for teens, young adults, and less‐educated workers, and especially strong for directly affected workers (those who see their wage rate increase automatically through the policy).

-

There is no evidence of these impacts becoming less negative in studies from more recent years.

Thus, there is still plenty of evidence that minimum wages cause “disemployment” effects, particularly for young people (who are specifically targeted by the Raise the Wage Act) and particularly when the wage hike is significant (see., e.g., what happened in Puerto Rico in the late 1930s).

Second, it’s imperative to understand all of the other channels through which minimum wages can work, beyond simply the number of jobs at issue. A 2019 analysis from the Congressional Budget Office (starting around Page 9) does a good job explaining these various effects, which include:

Worker effects. As Brian Albrecht recently explained, there are plenty of ways (“margins”) that workers can be adversely affected by minimum wages, even without overall employment levels (number of jobs) changing. This includes not only reduced hours, but also less-measurable things like fewer fringe benefits or job perks; harsher working conditions (e.g., having to work harder or having stricter manager oversight—great Twitter thread on that here); and fewer new hires (as opposed to layoffs). Jeff Clemens’ 2019 review of the literature finds these results to be common in the United States and elsewhere. Also, because it’s difficult for economic models to capture all of these variables (often due to a lack of data), both Albrecht and Clemens note that an empirical paper might conclude that minimum wage hikes didn’t hurt workers, simply because it didn’t account for the channel through which the worker was being hurt. In other words, it’s more likely that economics papers understate, rather than overstate, the costs of minimum wage hikes for certain workers.

Firm effects. Minimum wages also can affect the behavior of certain firms, particularly small businesses or ones that employ a disproportionate share of low-wage workers (e.g., fast food). As Cato’s Chris Edwards noted last week, small businesses tend to pay less than big ones, and research shows that they take a particularly hard financial hit (lower bank credit, higher loan defaults, lower entry and higher exit rates, etc.) from national minimum wage hikes. Given, as we discussed a few weeks ago, that “Big Box” and e‑commerce retailers like Amazon already pay about $15 an hour (or even more), it’s no surprise that the Big Boys are once again lobbying for minimum wage hikes that might hurt their smaller competitors:

Amazon, which already pays its employees a minimum of $15 an hour, urges the federal government to force that pay scale on its smaller competitors, in full-page newspaper ads. pic.twitter.com/7mIxLvl5dJ

— David Boaz (@David_Boaz) January 31, 2021

Josh Hendrickson adds that businesses can also try to pass along their higher costs to their customers through higher prices or stealthier things like longer checkout lines. (Indeed, the flipside of the common argument that minimum wages don’t cost jobs due to “monopsony” is that those same employers also have enough market power to force through price hikes.) Where this results in higher prices of basic necessities (food, clothing, etc.), low-wage workers—i.e., the very people minimum wages are intended to help—are disproportionately harmed. For example, one recent study found that McDonald’s restaurants passed on (through higher food prices) almost 100 percent of higher minimum wages, thus reducing workers’ “real” wage gains once the higher cost of living is considered.

Businesses might also turn to technology (e.g., machinery or self-service kiosks) in order to avoid employing (increasingly expensive) humans altogether—an outcome that could be more likely here because the pandemic was already pushing employers to automate low-wage jobs and because the delayed minimum wage hikes will give business owners time to invest in and adopt labor-saving technologies.

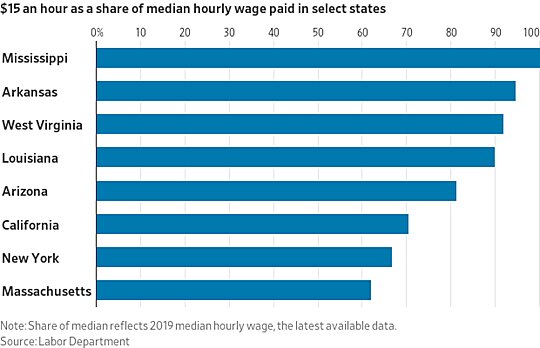

The extent to which these “stage two” effects will occur in a given place depends on all sorts of factors, most notably the prevailing wages in the place at issue. High wage/cost places like Manhattan might barely notice. But low wage/cost places like Mississippi, where the median hourly wage is just below $15, would face a serious shock:

That said, it’s definitely not just the lowest-cost places that will need to adjust: As noted above, about two dozen states currently have minimum wages significantly below the Act’s Day One minimum, and the vast majority plan to stay that way when the national minimum would hit $15 an hour in 2025. AEI’s Michael Strain adds other data:

According to data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics for 2019 (before the pandemic), in 47 states, at least one-quarter of all workers earn less than $15 per hour. In 20 states, half of all workers earn less than $18 per hour, and in 30 states, the median hourly wage is less than $19.

Although pre-pandemic trends posit that these wages will be higher in 2025 when the national minimum would hit $15 an hour, it’s certain that millions of American jobs and thousands of employers would still be affected, especially in low-wage/cost states and localities. The Raise the Wage Act considers none of this (which even left-leaning folks acknowledge is a big concern).

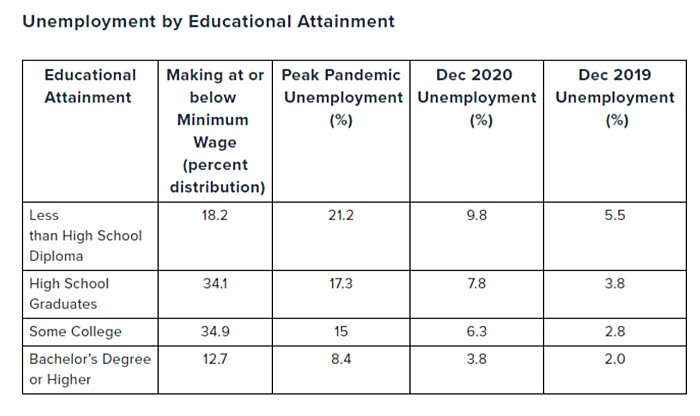

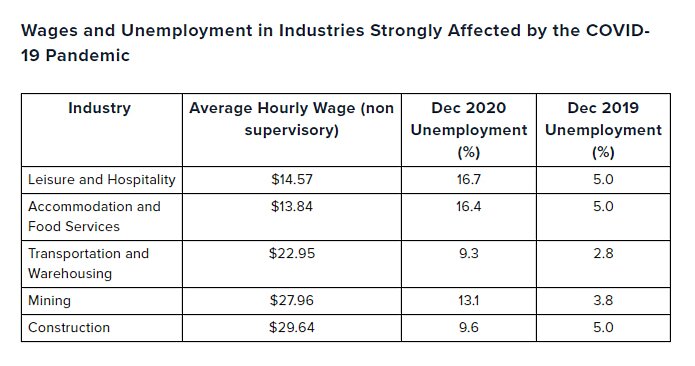

Finally, it’s important to note that the act would be implemented in the middle of a major economic downturn—one that, as these data from the American Action Forum show, has disproportionately harmed the very workers (low-education/skill) and industries (leisure/hospitality and accommodation/food service) that would most likely be affected by increased minimum wages:

As Bourne noted back in April 2020, minimum wage laws have more acute effects during economic downturns “because businesses are focused on restraining their payroll costs” and may “still hesitate to re‐hire at the same wages when the economy picks up again, because their earnings are down and their debt is higher.” Indeed, research shows that federal minimum wage hikes during the last recession had “significant, negative effects on the employment and income growth of targeted workers” in states that didn’t already have their own higher minimum wages.

Is This The Best Tradeoff We Can Get?

So there’s still no free lunch when it comes to minimum wages, but maybe these trade-offs are worth it? Answering that depends on what you’re trying to accomplish, and here I think minimum wages again underwhelm when compared to available alternatives. The most common minimum wage objective is to decrease poverty, but—leaving aside that even minimum wage supporters say the policy’s effect on poverty is uncertain or in dispute—using the minimum wage for poverty alleviation suffers from several flaws. First, and most obviously, channeling redistribution through employment ignores all the people outside the workforce, a number that’s extremely elevated right now due to the pandemic:

The millions of people in the chart above, of course, are primarily (though not entirely) low-wage/low-skill workers in service industries—i.e., the very people most likely to be hurt (priced out of the market) by minimum wage increases. That doesn’t seem like a sound anti-poverty strategy!

For similar reasons, even some progressives dislike the minimum wage as an anti-poverty tool. Here’s Clemson’s Michael Makowsky explaining why:

To my mind, the minimum wage is a policy failure strictly on the terms of (my own) left-of-center preferences. It is a victory of both political framing and strategy for coalitions against economic redistribution and the social safety net. That most of the left doesn’t even see this as a defeat makes it all the more devastating. Those outside the workforce are quietly placed outside the discussion and, in turn, are of secondary concern. More subtly, and perhaps more importantly, though, it builds into the policy construct a bargain that must be repeated and updated as national and local price levels change. Those repeated bargaining events force supporters to expend resources in each new iteration while, at the same time, giving their antagonists votes they can dangle when trying to secure support for their own pet policies. You want a higher minimum wage? Well, I’ve got a military procurement bill coming up next month that is slated to build 4 more F‑16s in my district…

Makowsky adds that high minimum wages might also push workers into informal, “gray” markets that “no longer operate under the layering of legal and regulatory protections we often take for granted, especially ostensibly pro-market types who think that labor and safety standards are emergent phenomena.” None of that, he posits, would be good for labor advocates.

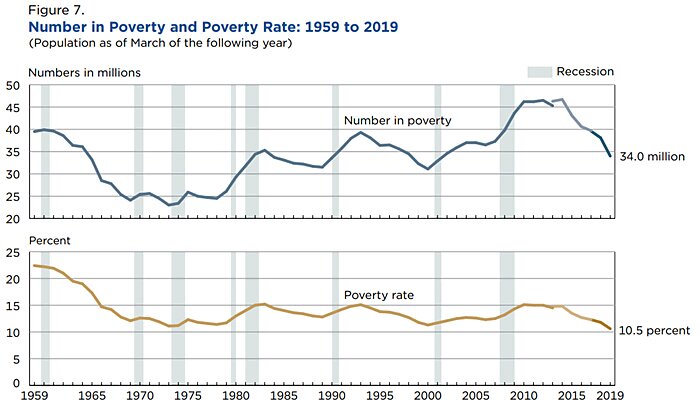

Finally, using a federal minimum wage increase to fight poverty ignores that the poverty rate hit an all-time low before the pandemic even thoughnational minimum wages hadn’t increased since 2009:

As we discussed a few weeks ago, moreover, incomes have been increasing steadily in recent years, with recent growth particularly impressive for those at the low end of the income scale.

Given these issues and the aforementioned tradeoffs, the federal minimum wage is a pretty poor anti-poverty tool, especially when compared to simpler, less problematic approaches like cash transfers.

Minimum wages are also a lousy way to fight inequality, given that wage hikes tend to hurt smaller businesses more than bigger ones, and that owners of minimum wage-intensive firms are typically not the super-rich but instead the merely-well-off. (Cool study on that here.) In other words, the Jeff Bezoses of the world not only avoid a “minimum wage tax” but might actually see their big businesses get even stronger. If, on the other hand, business owners can pass on higher labor costs through higher prices, the result is a regressive tax on consumers (meaning a tax that disproportionately hurts low-income individuals). In either case, the outcome is worse from a distributional perspective than a basic cash transfer financed by a progressive income tax.

Similar concerns arise for regional inequality, as a federal minimum wage would likely have a bigger negative impact on small towns and rural areas with lower wages/costs (and dimmer economic prospects) than “superstar” megacities where wages are already at or above the new federal minimums. The superstars would get even, uhh, super-er.

Summing It All Up

Despite common claims that minimum wage hikes are “essentially costless,” the bulk of academic research still shows that tradeoffs exist and go something like this: Higher federal minimum wages, particularly at $15 an hour, would benefit many low-wage workers but impose significant costs on other workers (particularly those out of the labor force or with the lowest skills), companies, and/or consumers—even if they don’t actually destroy low-wage jobs. (Indeed, that the $15 wage is phased in over several years is a tacit admission from Democratic sponsors that there will be some costs.) The specific channels through which those costs are imposed will vary, but it’s safe to assume that—especially given the current recession—they’ll be most acute for the people and companies already hardest hit by the pandemic, i.e., low-skilled workers and smaller businesses in the leisure/hospitality and accommodation/food industries, and those located in lower-cost states and localities.

Thus, by asking “and then what happens?” we can see the tradeoffs imposed by a federal minimum wage. And, whether the goal is fighting poverty or inequality, there’s little to indicate that a national minimum wage hike is the “best tradeoff we can get.”

Thanks, Dr. Sowell.

Chart of the Week

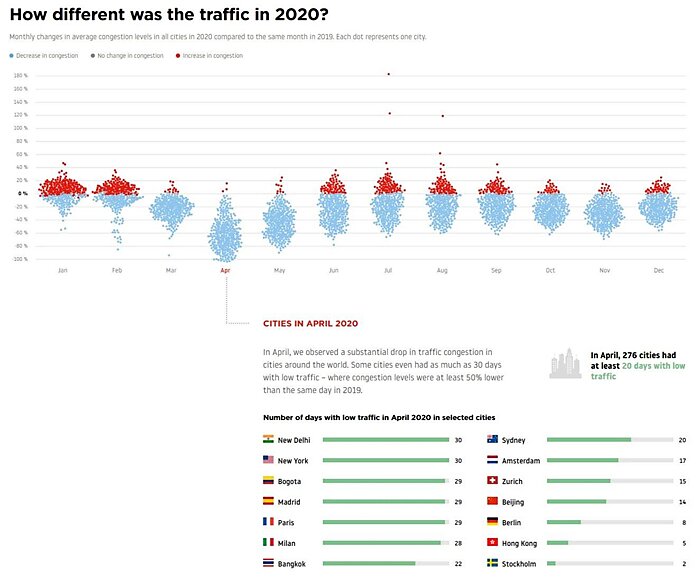

Incredible data on how COVID changed urban traffic patterns (in some places, maybe forever):

The Links

Me on Biden’s easiest trade test and his misguided embrace of “security nationalism”

Read Matt Levine’s last week of columns for all things GameStop

But also read the WSJ editorial board

Oh and this on Robinhood and clearinghouses

More support for a “First Doses First” vaccine strategy (and approving Oxford/AstraZeneca)

China’s risky crackdown on Jack Ma

The Fairness Doctrine was bad (radio) news

Great new study on immigrants and upward mobility

Shorter commutes means more older workers

Russia’s vaccine is looking pretty good